Frequently Asked Questions about Kamome

A short list of our most frequently asked questions.

To learn more about tsunami preparation, visit the Redwood Coast Tsunami Work Group.

Was the boat radioactive?

No. The boat was tested by the Del Norte Sheriff’s Office and no radioactivity was detected. This was no surprise. None of the debris that has been identified as from the tsunami has been radioactive and tsunami debris is no more likely to be radioactive than debris from any other source. The nuclear releases at the Fukushima Dai Ichi Nuclear Power Plant did not occur until long after the debris was washed offshore. No debris found anywhere in Japan outside of Japan’s Fukushima coast has shown any radioactivity either.

Were there any invasive species on Kamome?

There were lots of pelagic gooseneck barnacles on the boat. The species, Lepas Anatifera, has been observed in oceans throughout the world. The eggs are free floating and attach to any floating objects they encounter. There is no difference between the varieties in the eastern or western Pacific so it is not considered an invasive species. Kamome was not kept in the water when the boat wasn’t being used and the students always cleaned the boat after it was used. It was very clean when it was swept away by the tsunami and the barnacles only began to attach to the hull when it was far away from the coast. In April 2012, a portion of a Japanese dock beached on the Oregon coast. It was covered with non-native species and biologists removed them and the dock was destroyed because of concerns that some of the species could survive and displace local sea life. This is a photograph of the dock.

Are the barnacles that were found on Kamome edible?

Yes. The flesh inside the “head” has been described as tasting similar to lobster and these barnacles have been harvested for eating in Pacific Northwest and in Europe. Here is a serving of gooseneck barnacles in a Madrid, Spain restaurant.

Did anyone die in the boat?

No. At the time of the tsunami, the boat was not being used. It was tied up on the platform where small boats were stored. The force of the tsunami was so strong that the rope was snapped. This is a picture of the rope that was on the back of the boat.

How fast did the boat move?

The distance between Rikuzentakata and Crescent City is about 4,750 miles. It took the boat 754 days to float across the Pacific. If the boat moved steadily along the most direct path, it traveled a little more than 6 miles a day and only about a quarter of a mile per hour. It most likely took a much more complex path and sometimes moved faster, sometimes slower and may have traveled in circles or backwards part of the time. Here is a model of how the debris may have moved.

How much debris was washed into the ocean by the tsunami?

The Japanese government estimated that 5 million tons of debris were washed into the ocean by the March 2011 tsunami. About 1.5 million tons were swept far enough offshore to be caught in the large current systems that can carry material across the ocean. A recent study by Oregon State scientists estimated that at least 1 million tons is still floating in the northern Pacific.

How much debris was washed into the ocean by the tsunami?

The Japanese government estimated that 5 million tons of debris were washed into the ocean by the March 2011 tsunami. About 1.5 million tons were swept far enough offshore to be caught in the large current systems that can carry material across the ocean. A recent study by Oregon State scientists estimated that at least 1 million tons is still floating in the northern Pacific.

What does the tsunami debris look like in the ocean?

For the first three or four weeks after the tsunami, the debris was concentrated enough to be seen by satellites from space. But the ocean waves and currents quickly dispersed the debris so that it was no longer easily observable. This is a photograph that was taken about a week after the tsunami off the coast of Japan.

Why did the currents move the boat across the Pacific?

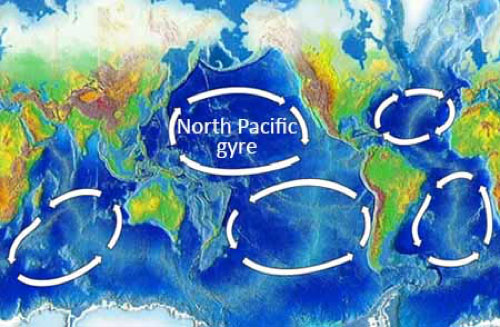

Large-scale currents called gyres occur in all of the ocean basins. The gyres are caused by the earth’s rotation and the predominant wind patterns. The North Pacific gyre covers most of the northern Pacific Ocean and is the largest ecosystem on Earth.

This is an animation produced by the International Pacific Research Center showing how the tsunami debris interacts with the North Pacific gyre and other ocean currents.

For more animations and background information about the tsunami debris dispersal, go to

IPRC - International Pacific Research Center, Tsunami Debris Models

Has any other tsunami debris arrived in California?

It is difficult to confirm debris found on the beach as coming from Japan. There are many items with Japanese characters on them that could have fallen from a fishing boat or come from Japanese aquaculture farms in North America. Over 2,000 possible tsunami debris sighting reports have been made to NOAA’s tsunami debris web site disasterdebris@noaa.gov but only 60 have been definitively linked to the tsunami by identifying marks. Boats like Kamome are the most common of the identified items because the registration numbers make it easy to trace them back to Japan at the time of the tsunami. Only one other confirmed tsunami debris tem has been found in California. It was another boat very similar to Kamome that was found on Humboldt County’s Dry Lagoon in June 2014. That boat is currently housed at the NWS Eureka Forecast Office. Here is a photograph of the Dry Lagoon boat on display at the Humboldt County Fair in 2015.

If there was a tsunami in California, would debris be sent to Japan?

It’s much harder to get debris from California to Japan than from Japan to California. The North Pacific gyre tends to concentrate debris in a region of the eastern Pacific known as the Pacific garbage patch. The southern limb of the North Pacific gyre doesn’t start heading west until offshore of the southern coast of Mexico. It would require a special pattern of winds in order to move debris that far south to be caught in the western limb of the gyre.

For more information about debris from the Japanese tsunami and marine debris in general, visit http://marinedebris.noaa.gov/current-efforts/emergency-response/japan-tsunami-marine-debris